Shock and Awe

Tumbling through the aftermath of surviving septic shock, a life-threatening acute medical crisis

It’s been four years since the helicopter took off east heading for Baltimore with me inside, unconscious and barely clinging to life. My eternal gratitude lies with the emergency room staff at Meritus who swiftly identified the infection that caused me to develop septic shock, and the pilot and flight nurses who literally cradled my life in their expert hands till my dying body was handed over at Shock Trauma, where a team of skillful colorectal surgeons were waiting to save my life.

I didn’t have an hour twenty minutes to be driven by ambulance to Baltimore. I heard the doctor ask EMS, who were waiting in the hall with my stunned husband, who could barely speak. “How long to drive her to Baltimore?” he called out, after determining that my colon perforation, caused by undiagnosed diverticulitis, and all my comorbidities, Crohn’s, hypermobile Ehlers-Danlos, and POTS, needed highly specialized critical care. I was struggling in respiratory failure and heading into heart failure. They could barely keep my blood pressure up. “An hour twenty,” was the reply, to which the doctor countered, “She won’t make that, call a pilot.”

This is the significance of why I named my podcast "The 1:20 Pod" which you can watch by clicking the link.

A fuzzy awakening

After resigning myself to the acceptance of death and my time on this planet being done, everything went black. I had no control here. Me. A person who, like many of us, felt better when I had some sort of control over a situation. But in these acute crises, none of us have control and I wound up slipping into acceptance. I was intubated, and terrified, and the blackness was warm and welcoming because at that point, I was so done. With life, with everything.

So I was quite surprised to hear a woman’s kind voice speaking to me, again in total blackness, but with different sounds, a beeping, in the background. My heart monitor. The voice said something to the effect of, “You were very sick, we didn’t think you would make it.” To which I nodded and my mind went black again.

The next thing I remember, the room was awash in bright brilliant light. After the murky day where I almost died, the sun seemed to be out. I heard my husband quietly ask me which credit card he should put the gas on.

Dear readers, please let me say here and now, if you know someone has recently undergone a life threatening sepsis crisis, talk with the family and help them start a GoFundMe. Right away. They won’t think they’ll need it, but please use my experience as the reasoning you can explain to them that they will indeed need extra money after their loved one comes out of their sepsis coma. Even if they have full healthcare coverage like I did for the hospitalization and doctors’ visits. We finally launched a GoFundMe this year. Because we are still trying to overcome debt we heaped upon high interest low-limit credit cards to pay for all sorts of expenses to help me through my lengthy recovery. And the debt remains tremendous and worrisome. Thank you to all who have donated thus far to help us finally put this part of my sepsis crisis behind us.

No one gets up out of the hospital bed after surviving sepsis and goes back to life the way it was. It takes months, even years, if we ever get back to “normal” at all. Sepsis survivors and their families are forever changed. And they need all the help they can get. So please ask them, can we start a GoFundMe for you?

Cry me a river, I was really good at it

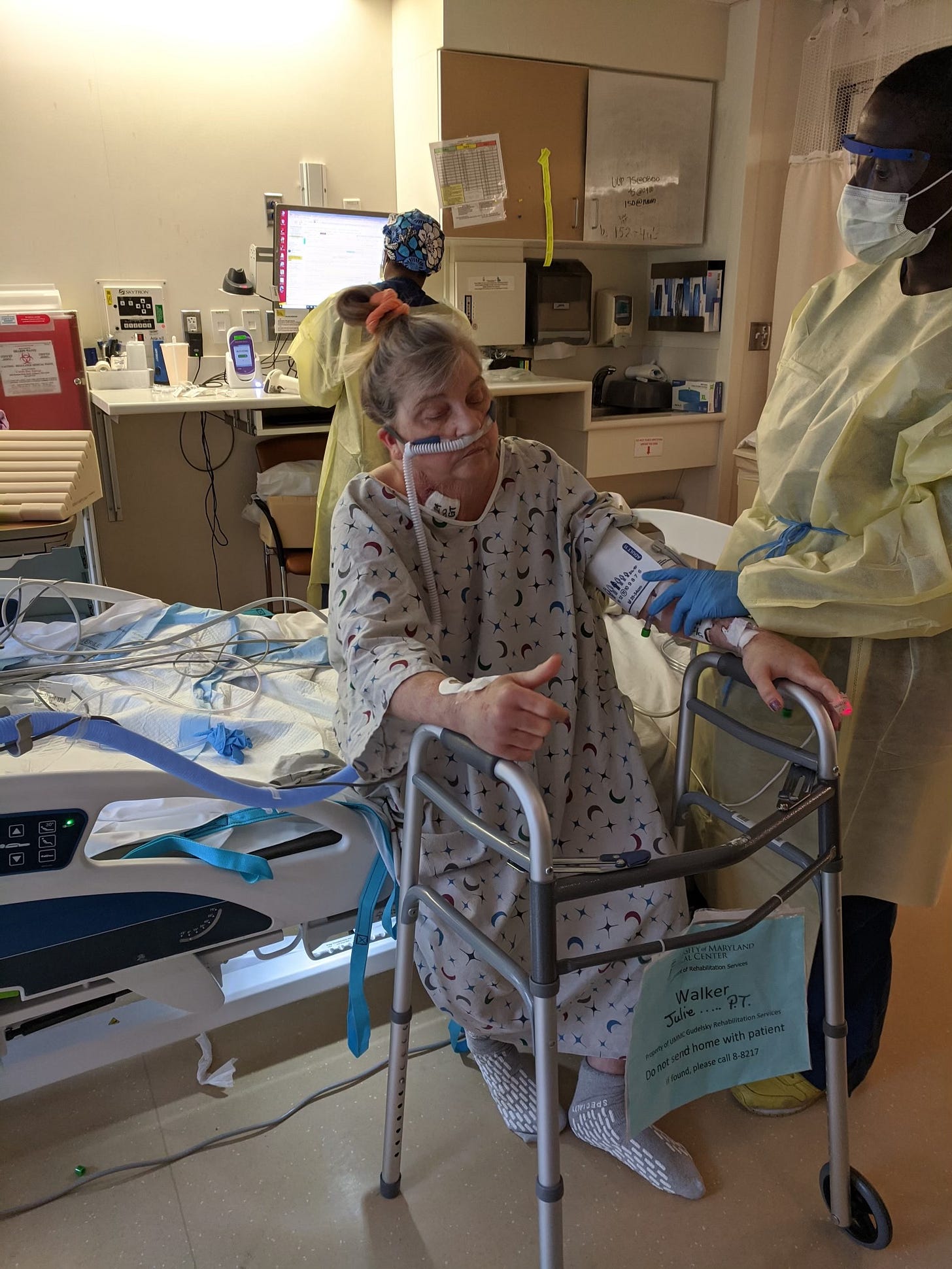

My days spent in SICU at Shock Trauma were a blur. Nurses taking vitals, doctors visiting, and monitoring my progress. My nights were plagued with chilling, horrific nightmares that I believe were caused by the strong antibiotics I was given to treat my infection. Vitally necessary antibiotics, but not the most pleasant side effects. I was tended to gracefully and carefully by a stellar team of doctors and nurses like none I’d ever had before. I couldn’t walk, even with a walker, so I was “lifted” with a full body Hoyer lift that wrapped me up like a burrito and whisked my motionless body around the room.

After eight days on this unit, I spent another week on a step-down unit before being transferred to the University of Maryland Rehabilitation & Orthopaedic Institute where I spent three and a half weeks, six hours a day, six days a week, in physical therapy and occupational rehab learning to walk again, to feed myself again, and to regain strength. I couldn’t remove the tin foil tops off a juice container. I couldn’t lift my silverware. My lungs were damaged, which warranted a lot of visits from respiratory therapists, who studied my lung exercise attempts with a furrowed brow. I could barely budge those little balls inside the clear, plastic chambers. And to top it all off, I had a temporary colostomy and had to figure out how that worked with the help of an ostomy and wound care nurse and my husband. He was my “eyes” during this time, because I had cataracts in both eyes clouding and obstructing my vision.

The sight of the stoma, even through cloudy cataract covered eyes, was jarring. A bright red, swollen piece of intestine popping through my abdominal wall. I also had a 12 inch incision that ran from my breastbone to well below my navel. My belly button was gone, crimped in a slant with staples. The doctors planned to do another surgery seven months later to reverse the colostomy. Which they did in December, successfully, and I will elaborate on that more in another post. If you or someone you know is struggling with an ostomy, and you live in the U.S., please check out the United Ostomy Association of America to find a local ostomy support group near you. My father had a permanent colostomy placed back in the 70s due to colon cancer and they didn’t have the support back then, that they do now.

I didn’t have diabetes before sepsis, but afterwards, it was like I’d been eating ice cream and chocolate bars all my life. My glucose readings were in the 300 to 500s and the nurses needed to give me insulin. Survivors of severe sepsis or septic shock often have blood sugars that are off the charts. And I wasn’t even eating much, because I could barely feed myself due to extreme weakness, and food just didn’t appeal to me. I had some damaged molars making it difficult to chew. I’d shakily dangle the spoon to my lips to slurp a few bites of jello or mashed potatoes, sip some milk, and that was it. My arms were still full of IVs so they were hard to move and I was unable to sit up on my own. My urine output was like Niagra Falls. The nurses had to empty the bags almost every hour. My kidneys were reeling from the crisis, like, WTF just happened?

Septic shock is like a nuclear bomb going off within your body and survivors are left salvaging whatever they can in the aftermath. It blows your body, and your mind, apart.

After settling in at the rehab hospital, I would wheel myself into the gym every morning after breakfast, and another failed attempt to properly deal with the colostomy on my own. I worked hard using a walker, doing ‘wheelchair dance,” and stacking small objects on a table while standing up (braced by the therapist) to strengthen my legs. It was difficult and exhausting work. I grew nauseous at times. The first time the therapists had me walk while holding onto parallel bars, I felt the familiar feeling of acid and saliva surging in my mouth. The room started spinning. My POTS was hitting hard. My blood pressure dropped while my heart rate skyrocketed. The therapists immediately sat me down in my wheelchair and raced me back to my room where I unceremoniously threw up in the toilet just as my husband arrived for his first rehab visit.

After a six hour day in the gym, I’d wheel myself back into my room and lie flat on the bed with my eyes closed, only to have one doctor, a real taskmaster, walk in at that very moment, and admonish that I shouldn’t “lie around” if I wanted to heal. Internally, I was screaming. I’d just spent the last six hours in the gym, didn’t that count for something?

Eventually, a few weeks after I came home, sometime in July, my hair fell out. More like, broke off midway and my once thick hair thinned rapidly, leaving me with a wiry mess perched atop my head like a grey bird’s nest. I avoided looking in mirrors. I nearly had a nervous breakdown every time I saw the gnarled tarantula-like clump of hair surrounding the shower drain. I was unable to do anything strenuous, like shower myself, my husband had to help me. Afterward, my daughter washed my hair in an inflatable shower basin while I lie prone on the bed.

I cried every single day, without fail. I was terrified, living in constant panic. I wondered why I survived, and some days, I wished I hadn’t. I had PTSD. I didn’t know it at the time, but I was suffering from Post Sepsis Syndrome.

Carrying a cross too much to bear - looking for “the helpers”

It was well into summer, late June, when I finally came home and our friends were all out of town on trips or at the beach. Which depressed me even more because I would much rather have been on a beach than the place I was drowning in, weak and feeling like “damaged goods”. We were grateful to receive some meals when people were in town, but the challenges of day-to-day living were thrust upon my husband, and our two daughters living with us. The one who had just graduated from college and the other with two years to go. We were living in a small apartment over 30 miles from former neighbors and friends. It was cramped living, but it was the only place we could afford. My son and his fiance lived in the next town over and they did what they could to help. It was also the height of Covid, 2021, and we had to be careful with visitors as a new and more virulent strain, the Delta variant, was rising in popularity and had already taken out a distant family member’s in-law. One friend did Facetime with me each day which helped quite a bit. And I sought out the help of a retired social worker/Deacon who we had known for years at our local church. I couldn’t find any mental health providers in our area who accepted Medicare. The Deacon was a welcome relief and a good fit, to talk about all my deepest thoughts and fears surrounding dying, and my current medical condition which I believed would last forever, making me a burden on my family till my end of days. Our entire family was living in a state of “suspended animation.” My husband went to therapy sessions with me so he could gain a better understanding of my triggers and what was lurking inside my brain that day.

I was incredibly weak and suffered upper back pain from osteoporotic fractures I had sustained before sepsis. Sitting up in the car for my husband to drive me to weekly doctors' appointments and therapy was unbearably painful. I had no support from a core that had been sliced and diced to save my life. I was unable to accompany my husband and son taking our youngest back to the dorm at college, something I had always greatly enjoyed. But I could only tolerate sitting up maybe ten minutes max, before pain set in, rendering my arms numb and useless. I needed frequent bathroom breaks and was still trying to get accustomed to the colostomy. I sobbed endlessly when they left. Our other daughter stayed with me that day. Torrents of rain hit the windows and mirrored the endless tears that flowed down my cheeks. I didn’t want to be seperated from my youngest. I was terrified I’d never see her again.

I was unable to sleep much during this period. I’d sleep fitfully at night, through nightmares of people melting, and other frightening ordeals, and waking at the break of dawn to start another day of ritualistic sobbing. I didn’t nap even though my body was ready to collapse. I no longer cared to watch television or movies. I laid on the couch and stared at the wall through yellowed, cloudy, cataract damaged eyes. I had to undergo a lot of medical procedures which were critically necessary for my recovery and to prepare for the colostomy reversal, another major surgery. I needed iron infusions, which terrified me, a colonoscopy (interesting when you have a stoma), monthly lab work, physical therapy. The list was endless and the miles we piled onto our 16 year-old minivan ran into the hundreds and then thousands.

Be yourself, and find people brave enough to listen

After you survive sepsis, find people who let you be “real.” And I was unapologetically “real.” I was not of the “positive” mindset crowd and the mere mention of “be positive” was enough to send me flying into a rage or a torrent of tears at whoever had the audacity to suggest it. I was dealing with unfathomable pain, physical weakness, fear, anxiety, a body that didn’t work the way it did before, and all sorts of tests, procedures, and doctors visits that required long car rides more than 70 miles one way. My kids were trying to pick up the pieces, my husband was still stunned, and frustrated because he felt unable to help me in any meaningful way. Money was very tight, our two kids who had graduated college in May were looking for jobs, trying to “save” us financially from going off the cliff. Even while undergoing the duress they had just experienced with their mom almost dying. Our “baby” the youngest, after heading back to college, wound up crying through her own battles trying to keep her grades up and learn inorganic chemistry and quantum physics. Luckily she attended a small college and I had alerted the science department and the Dean about what had happened, and they helped our daughter tremendously by providing any type of support she needed.

My family was living in an echo chamber and it sometimes got loud and very messy. That’s what emotions are supposed to do. We have them for a reason and I fully believe in expressing them in dire situations like this. Our daughter who had just graduated felt woefully inept trying to make some noodle soup for me one morning, and I was too weak to help her. She knew how to make it, but her nervous system shut down and she was left dumbfounded by the stove. It was lot for a family struggling to make it, to undergo.

My family was so happy that I survived, they wanted to celebrate my 59th birthday in September. My now daughter-in-law asked her mom to make a cake. It was a most beautiful cake. And they conspired to get Maryland blue crabs, and all my favorite treats, to host a surprise party outdoors at a local park. My youngest daughter joined via Facetime from her college dorm. Ironically, my birthday falls on September 13th, World Sepsis Day. It made me feel so much better, probably one of the rare days that I didn’t sob endlessly morning to night. I was still on a mobility scooter, still very weak. It was hard for me to sit up and eat very much. I was always concerned about what I ate because of the stoma. I had a few bites of crab and some cake, it was the best time I’d had since the college graduation picnic our little family enjoyed a week before I nearly died from sepsis. The air was heavy with a blanket of humidity, typical Maryland weather. Even so, I managed to walk a few steps along the riverbank trail. It wasn’t much, but it was progress. Mostly, I gained enormous enjoyment watching the kids enjoy themselves, eating and joking around like before. Before I nearly died.

Going home to our apartment, I was extremely tired, and my back hurt, but I was touched by what my family had done for me that day. And I resolved to try as hard as I could, to get stronger.

Stay tuned for more posts about sepsis recovery….

Special Note: Post Sepsis Syndrome is a relatively unknown entity in the medical world, and one New Zealand follower on Instagram is trying to raise awareness with a petition to put Post Sepsis Syndrome on the radar of the World Health Organization. They have over 1,700 signatures. Would you please help by signing the petition and sharing my essay so that more will sign?